In the business world, collaboration is a buzzword you hear frequently. The exchange of ideas and specialized knowledge has been shown to lead to greater efficiency as well as better products and results. Pixar and Google are known for designing office spaces to maximize encounters among employees in different divisions to encourage creativity and collaboration.

Collaboration is also a hallmark of a Montessori elementary community. The mixed-age groupings are a feature of Montessori at all levels, but the elementary is intentionally designed to support collaboration because it is a need that is highlighted at this age.

Montessori Theory

When Dr. Maria Montessori was developing her approach, she observed with her keen scientific eye the characteristics that marked each age group. The calm orderliness of the child from birth to 6 years old gives way to the elementary-age child with a fully formed social personality that craves interaction.

In the first six years of life, the child is focused on himself. He is aware of others, but they are not the center of his attention. In the Children’s House, the child’s work and lessons are mostly individual, though he may work in the company of others. Montessori noticed that there is a shift in the next six years in which the child begins to attach himself to others and wants to be surrounded by people. In elementary, the child’s work is mostly collaborative, unless he is working on perfecting individual skills.

“Education between the ages of six and twelve is not a direct continuation of that which has gone before, though it is built on that basis,” Montessori wrote in “To Educate the Human Potential.” According to Montessori, the first period of life is for the “acquisition of environment,” whereas the next phase is for the “acquisition of culture.” Meaning, the elementary years are the time when a child is eager to learn about how people throughout history have contributed to society and how the child will one day do the same.

Montessori observed that elementary children begin to separate from their family and are drawn outward toward society. Group activity becomes very important because children love to join one another. Montessori considered this behavior to be so pronounced and universal that she referred to this urge as an instinct.

She noted that the elementary child has a “need to associate himself with others, not merely for the sake of company, but in some sort of organized activity. He likes to mix with others in a group wherein each has a different status. A leader is chosen, and is obeyed, and a strong group is formed. This is a natural tendency, through which mankind becomes organized.”

How Montessori Elementary Fosters Collaboration

- When a guide, or teacher, gives a lesson, she selects a small group. The children in the group may not be the same age or grade. They may share an interest or a certain level of readiness. Lessons are rarely given to individuals, unless it is a review. Whole class lessons are equally as rare, unless the guide is trying to orient the class at the beginning of the year or is starting a new class.

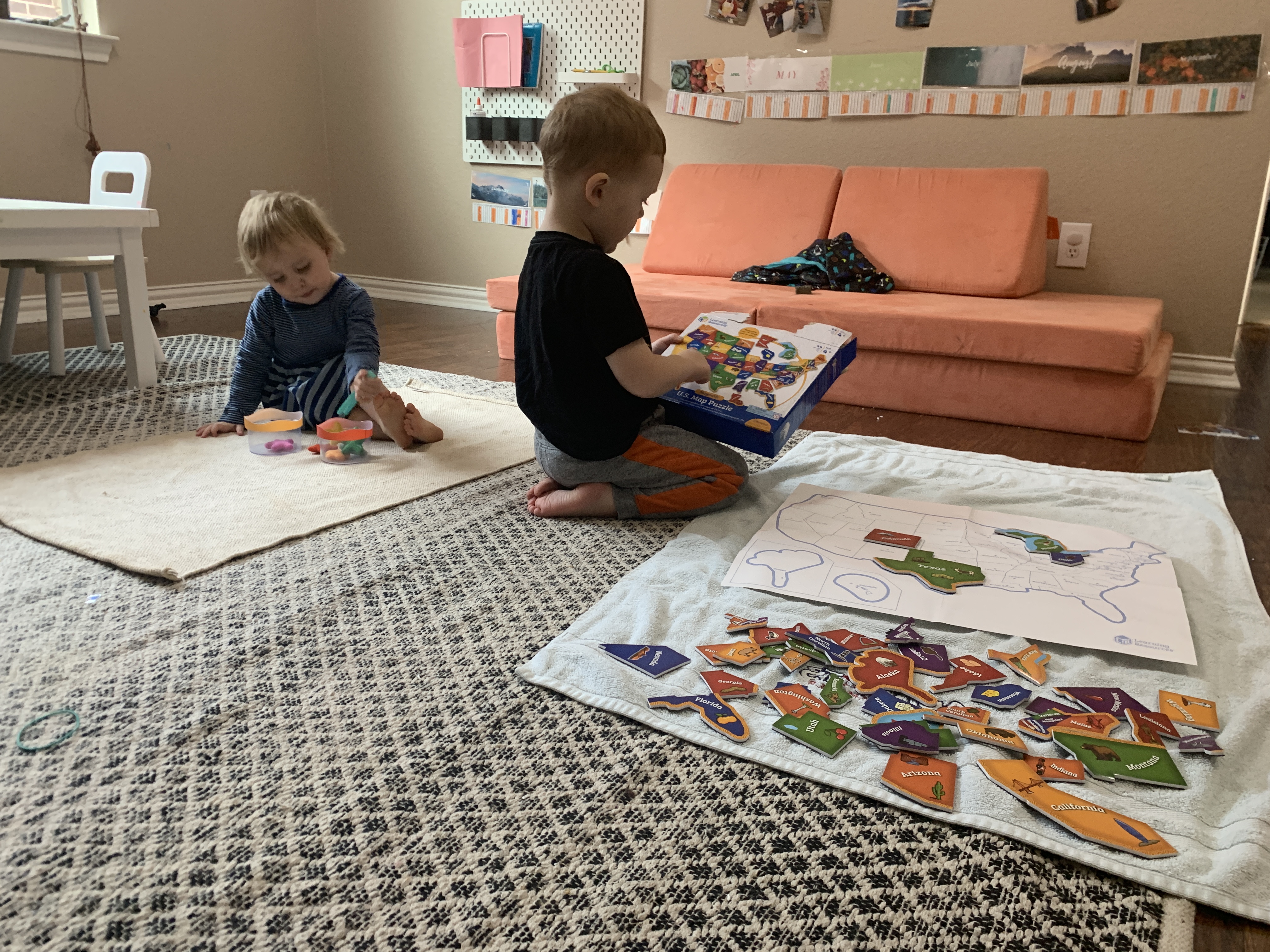

- A variety of tables with multiple chairs or seating are available throughout the room. Children have the freedom to move around the room and choose their own seating arrangements. Some classrooms offer the opportunity to work on the floor and spread out or work outside if there is outdoor seating.

- Children have the freedom to communicate. There is no expectation of silence as exists in most traditional classrooms. Children do not need to wait until they are called on to answer a question. Children plan, organize, and consult with each other all day long and are free to ask the adults in the classroom for guidance if they are available.

- Children have the freedom to move around school grounds if they have asked permission to make the adult aware of their whereabouts and purpose. They may borrow resources from other classrooms or conduct a survey of children in another classroom.

- Children are not limited to the materials available to them in the classroom. They are encouraged to organize what is called a Going Out. They may arrange to visit a museum or a library, for example, to extend their research, or they might interview an expert in the field of a topic they are pursuing.

- In the absence of grades, regular testing, assignments, and required homework, children are not seeking to outperform one another. The spirit of cooperation permeates a Montessori elementary classroom. Peer tutoring happens very naturally. A child who is challenged by a concept in math can ask a neighbor for help. Older children are mentors for younger children who can observe the kind of work they will be doing in the future.

- Children with similar passions or those who need practice in overlapping areas can be paired by the guide or often discover each other on their own!